(This is a slightly cleaned up version of my two Bluesky threads on Jennell Jaquays, preserved in a hopefully easier to read format. Thank Amanda P for reminding me that having these things stored outside of social media is a good idea!)

In 2024, we lost Jennell Jaquays. To just say that she was a TTRPG and video game designer would be doing her contributions a disservice, but that was my main intersection with her legacy. Here I’ll talk about why, historically, her work was such a blessing to dungeon design and why her stuff is still required reading today if you’re interested in making your own dungeons.

At the outset, I should mention that Justin Alexander has a famous article about this, which has some controversy to it that I won’t cover in this post. It’s regularly cited, so you should at least know it exists. It’s important to note that this article used to be called “Jaquaying[sic] the dungeon”, by the way.

So why is this one designer so important that someone would (originally) name an entire series of level design articles after her? To understand this, we need to look at what existed before Jaquays entered the game.

Pre-Jaquays Dungeon Design

Say you just bought the three “little brown books” that comprised the original release of Dungeons & Dragons and want to know how to go about building your own dungeon. The average D&D player had access to few sources of advice on what a good dungeon was like in the 70s, fewer than we will even discuss today. The easiest to access was the sample dungeon level that came with book 3 of OD&D: The Underworld and Wilderness Adventures (UW).

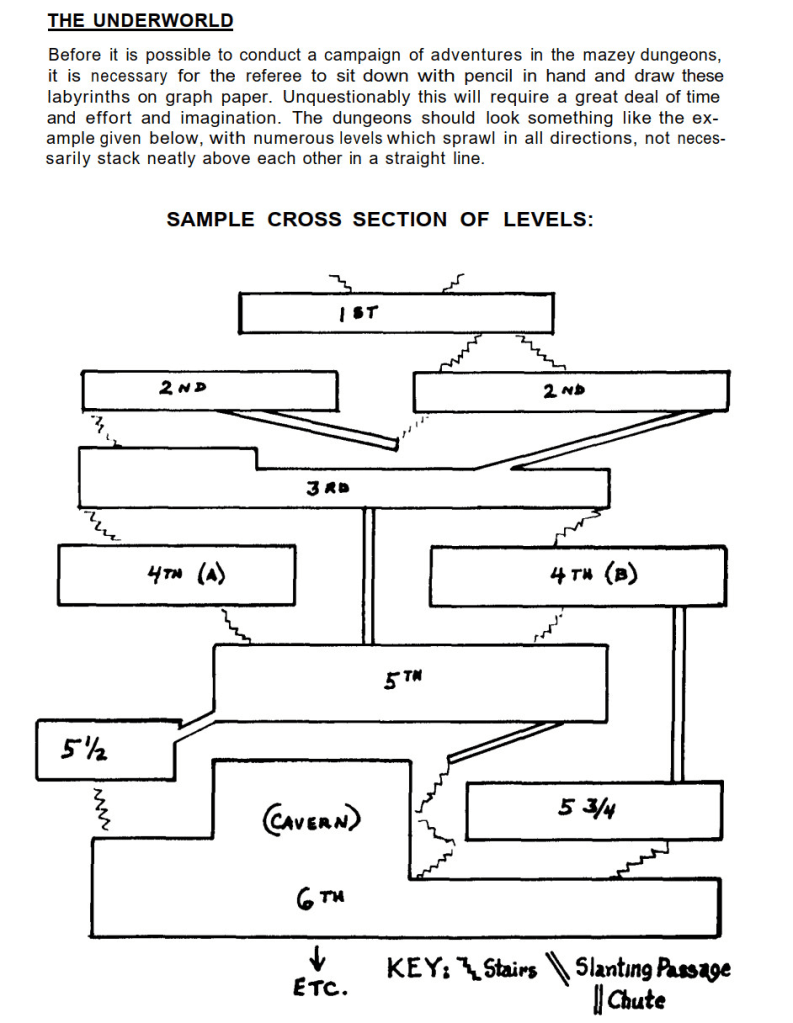

UW advises that the early stages of a campaign be set in a massive multilevel dungeon next to a town the players use as a base (a premise that explains a lot of things I make). Players would conduct expeditions into the dungeon, find treasure, then try to get back without dying. It recommends at least 9 interconnected levels as seen below (vertically):

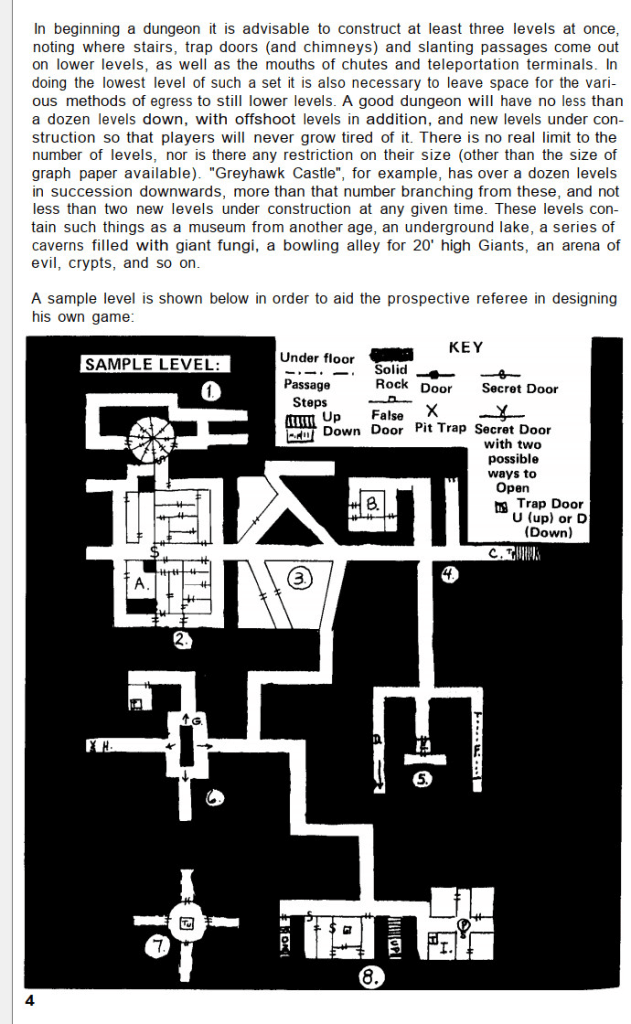

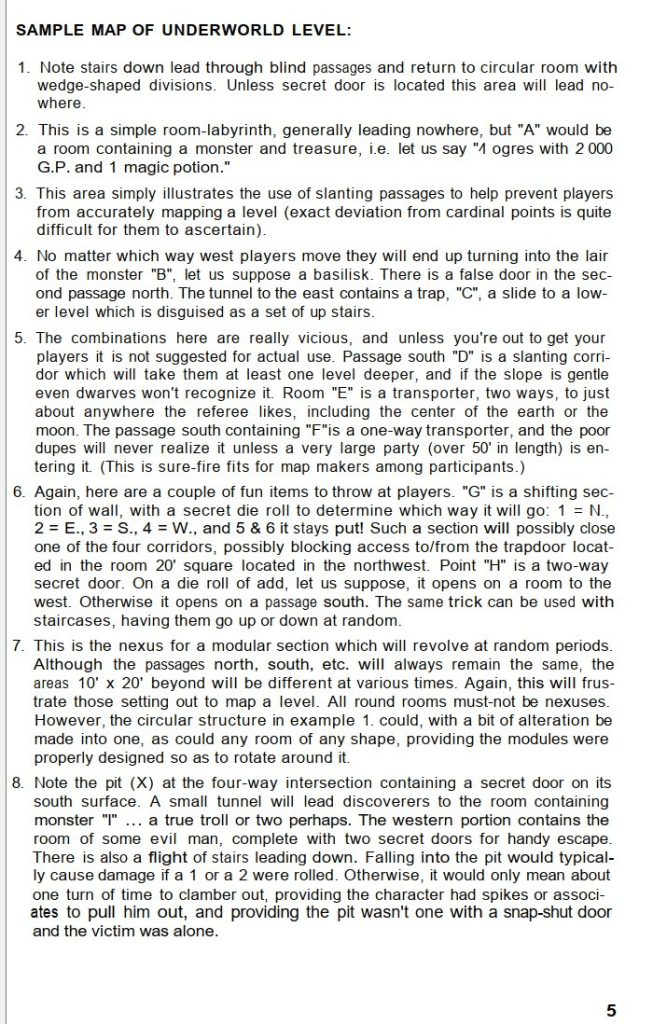

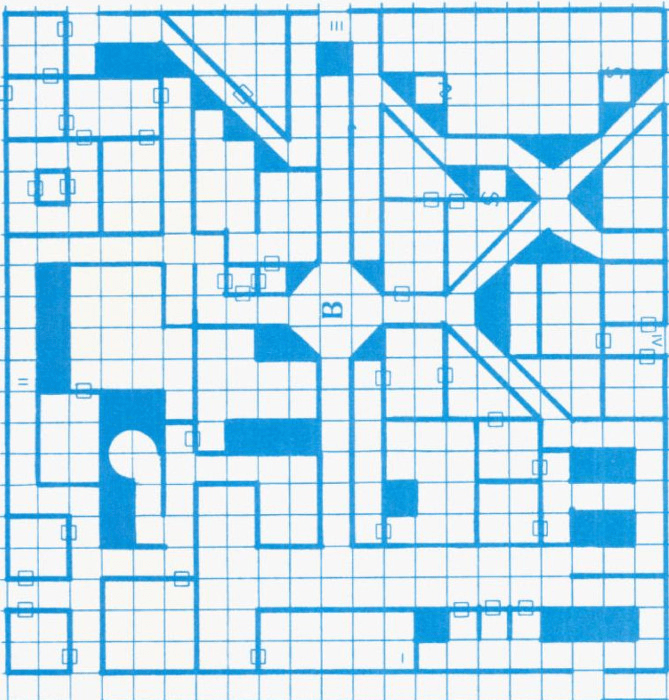

Here Gygax is advocating for pathing choices on a macro level. The choices shouldn’t be equally available or move uniform ways — notice how you might not be able to access half of floor 2 until you go to floor 3. You might also go straight from 3 to 4. Think SMB1 and its warp pipes. After this, we get to the lower level of dungeon design, which is the individual floor map. Here’s Gygax’s sample level:

We can see pathing choices coming into play here as well. Starting from the entrance to the northeast, you’re picking between terminal hallways on the left and right, then you’re moving to two sets of small loops, one of which branches off South. This might seem simple, but consider that OD&D is presenting the simple movement across and mapping of hallways as a novel and challenging task. Time is measured by inches moved on the map, which triggers encounters and requires expenditure of light sources and food, so already there is a lot of stuff going on here for new players (i.e. everyone).

Looking at the notes for this sample floor, you can see this in how Gygax describes what is interesting about these rooms. Again, not everything has to be exceptionally interactive because he’s emphasizing the interactions that arise from the basic movement and mapping procedures. This is all stuff that is meant to share the stage with the exploration mechanics, rather than stand entirely on its own.

If you’re wondering why none of the rooms in this key talk about monsters or treasure, it’s because even this premade map requires you to use the dungeon stocking procedures provided later. I think this was low key a very good choice, as it takes a firmer stance on the dungeon being just the setting — the things that inhabit it and which players might steal from it should be seen as more dynamic and mercurial. The GM should think of stocking the dungeon as a thing they can expect to do regularly. Either way, as far as providing a premade dungeon goes, this is all you get for OD&D.

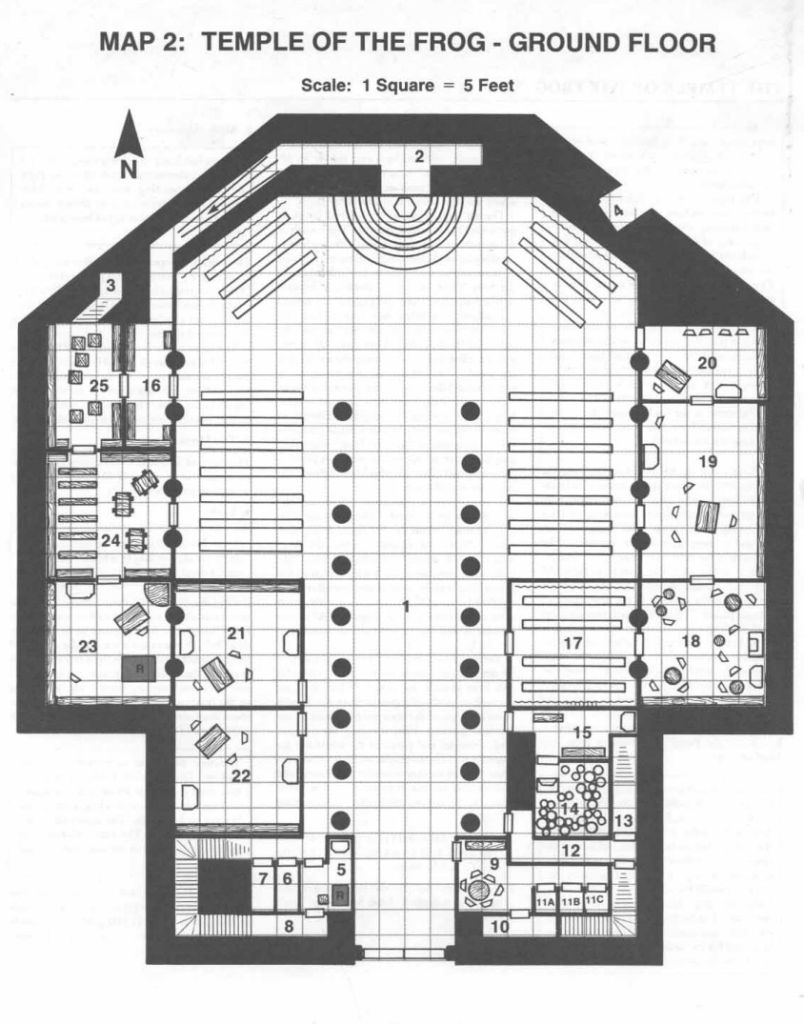

So let’s take a look at what kinds of premade modules you could find separately and purchase. First up is Dave Arneson’s Temple of the Frog from the Blackmoor Supplement (1975, screenshots from a reprint). With Frog God, we already see a move to our more modern conception of a premade dungeon. It has backstory, written out keys describing situations in each room, and a map that is more naturalistic. Arneson puts a little more emphasis on the situations playing out in each room than using complicated corridor arrangements to challenge the players’ mapmaking skills, which we will see become the dominant trend in dungeon design as we move forward.

Other new things we see in this module include a lot of text about the location’s social hierarchy and cultural background, environmental storytelling with intentionally placed objects, and defined factions. As far as the actual quality of the module goes, Gus L has a review of it you can read. Gus also thinks of this as much closer to the modern conception of a dungeon module, with a layout that evokes a real location playing a part in a greater regional situation and which hosts multiple factions for the players to interact and align with. However, Gus criticizes its really basic keying (though we’re going to see something even simpler next) which does not really evoke much interesting interaction outside of combat.

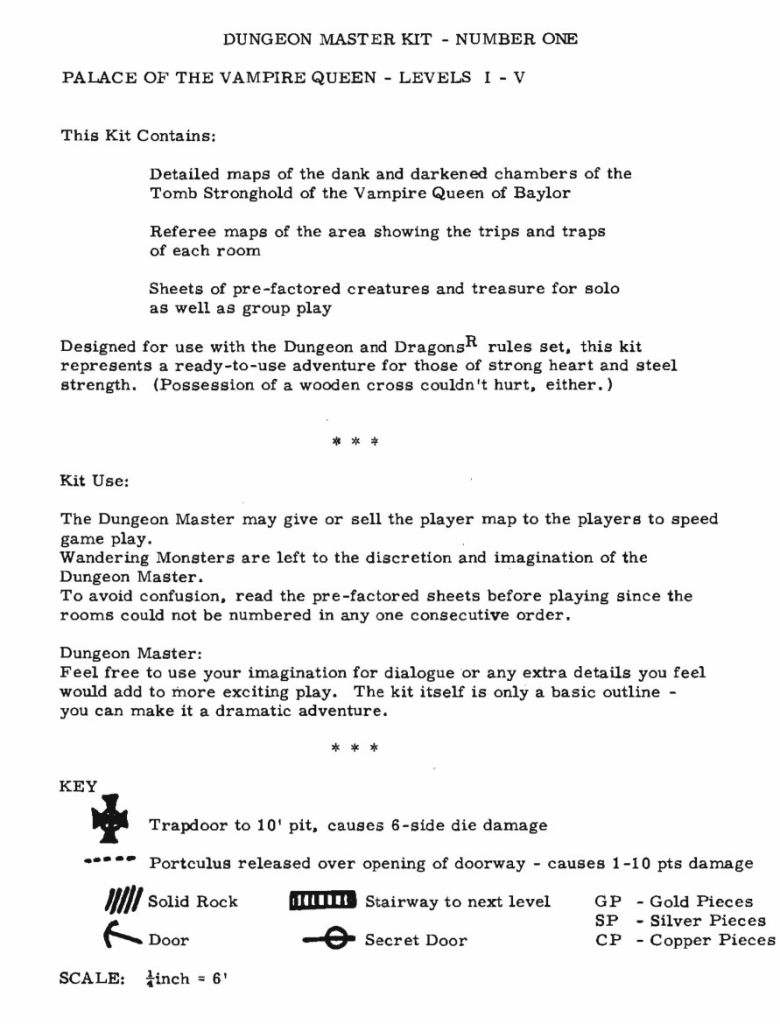

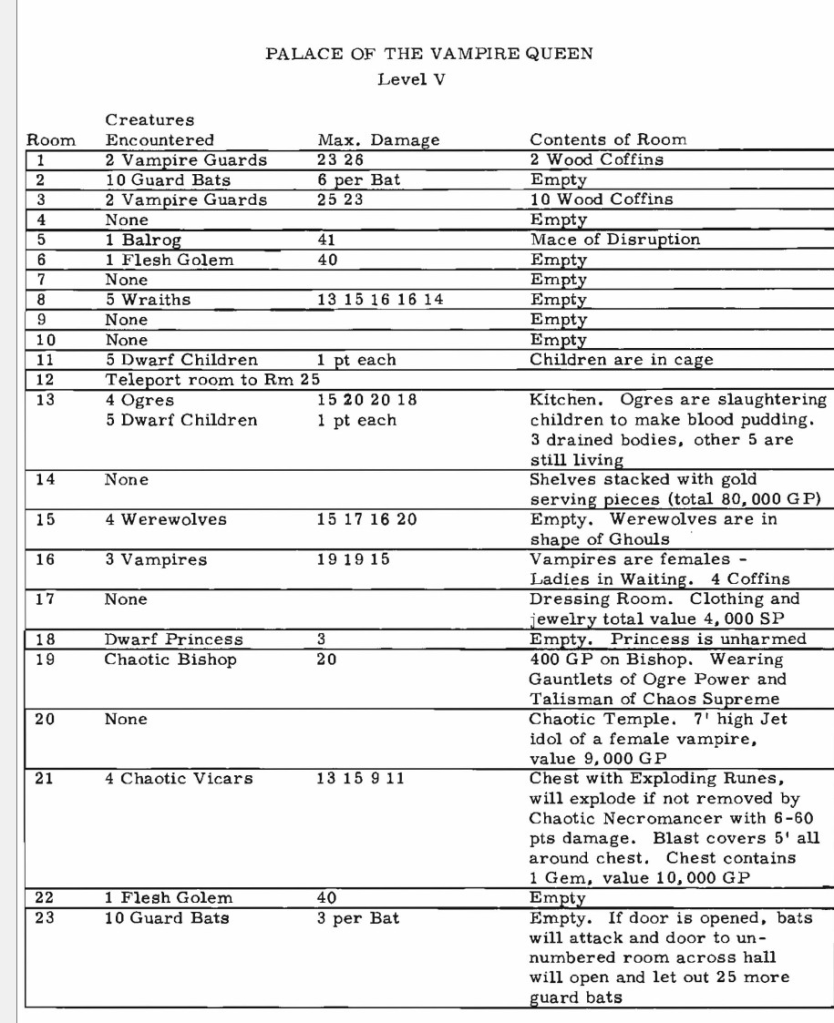

1976 sees the release of Palace of the Vampire Queen by Wee Warriors. This book presents itself as a readymade adventure but also a “kit” used as a tool of convenience. Like Frog, it has some back story to give context, however this is as detailed as the module ever gets about what’s happening:

Unlike Frog, the key is actually quite terse. The intention here is that you read the dungeon keys and then figure out what the actors in the dungeon keys must want or need based on the above backstory, filling in the blanks with your own ideas where necessary. I’m not super against this, as I think this key format at least prepares the reader for the fact that they’ll have to do some work before bringing it to the table. The key reads like what it actually is: the basic skeleton you’ll use for each room to construct the actual room descriptions. Of course, at this point in time it might not be very clear to a new GM what an interesting room actually looks like, or how to write an interesting room key for later use.

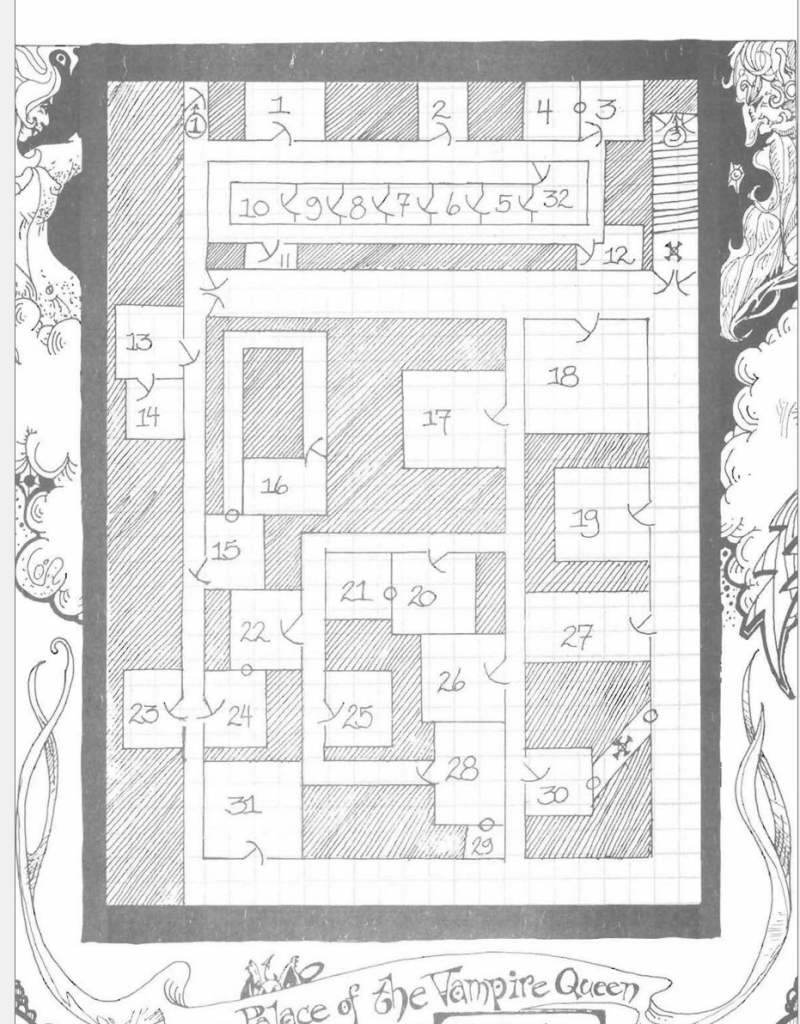

The levels mostly look like the sample below. Here we see another hallway-heavy module like Gygax’s, but one that presents far more choices about what to do next. “What door do we open” is a common question players will ask. We’ve moved from a labyrinth layout to something more akin to a shopping mall.

The shift to this “opening doors” style layout is also a shift of focus to the dungeon room as a kind of discrete unit of content. And while the key is terse, you can see how a DM would be able to stock each of these square rooms to be its own little story/scenario to interact with. While this adds a lot of freedom of player choice, the choices are kind of flattened. You almost always know what direction you’re entering a room from, and the choice between two adjacent rooms is not very interesting. You know you’ll look in both, the question is just, which first?

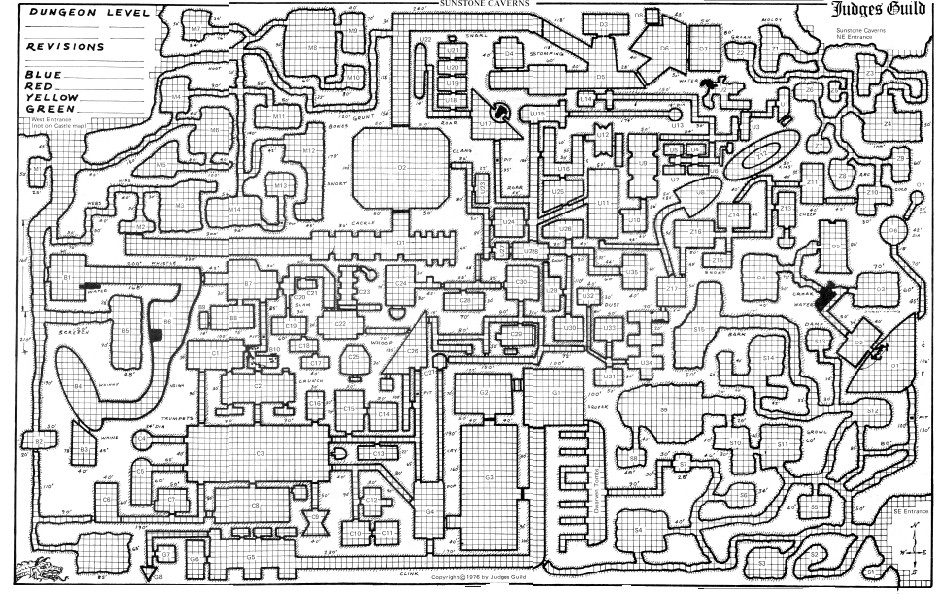

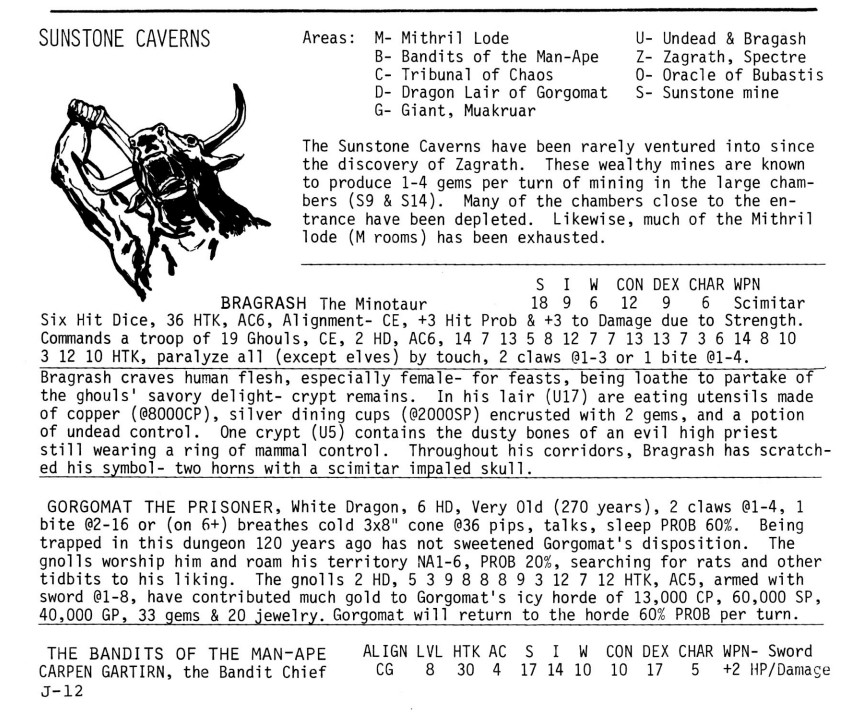

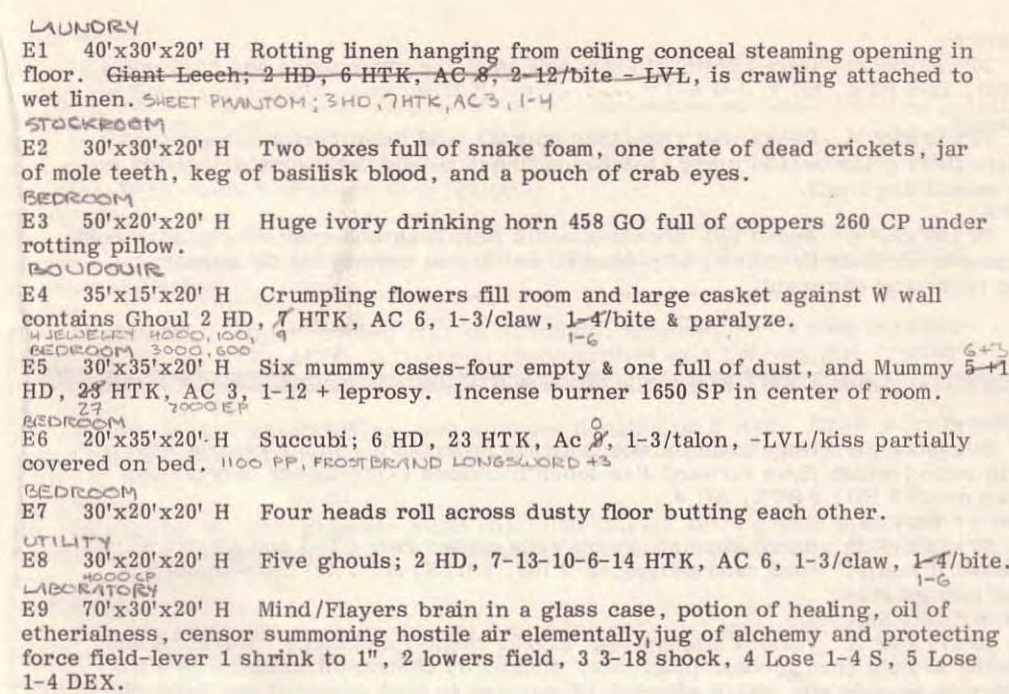

There are a number of releases after Vampire Queen, usually tackling things other than dungeons (wilderness exploration, cities, etc). The most interesting and relevant to this discussion, however, are the blank maps that were being put out by TSR and Judges’ Guild. Here are a couple samples:

The second of these, the Sunstone Caverns, has a few rooms described in an accompanying booklet which resemble modern dungeon room keys, though there is no room by room key other than the annotations you see on the map above.

Fittingly, the kind of layout you see in the examples above are probably the closest predecessors to what we’ll see in Thracia (a later Judge’s Guild release) in terms of map design.

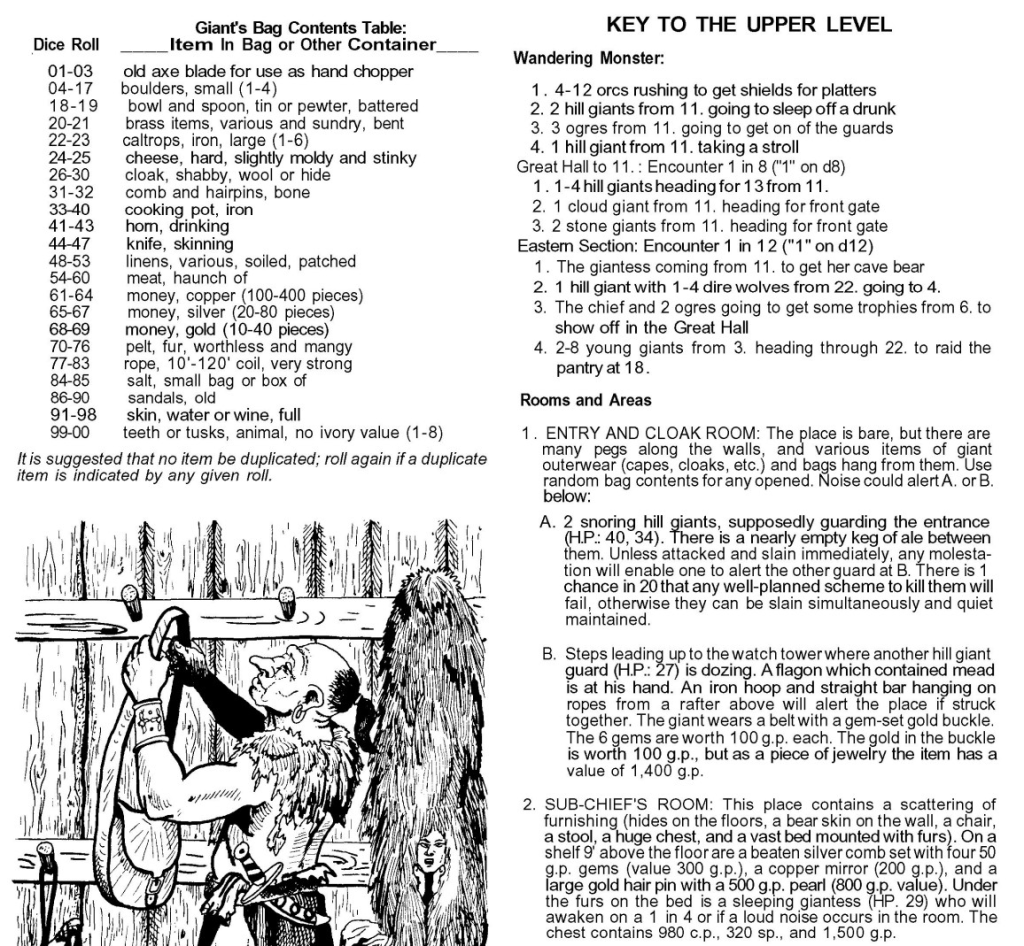

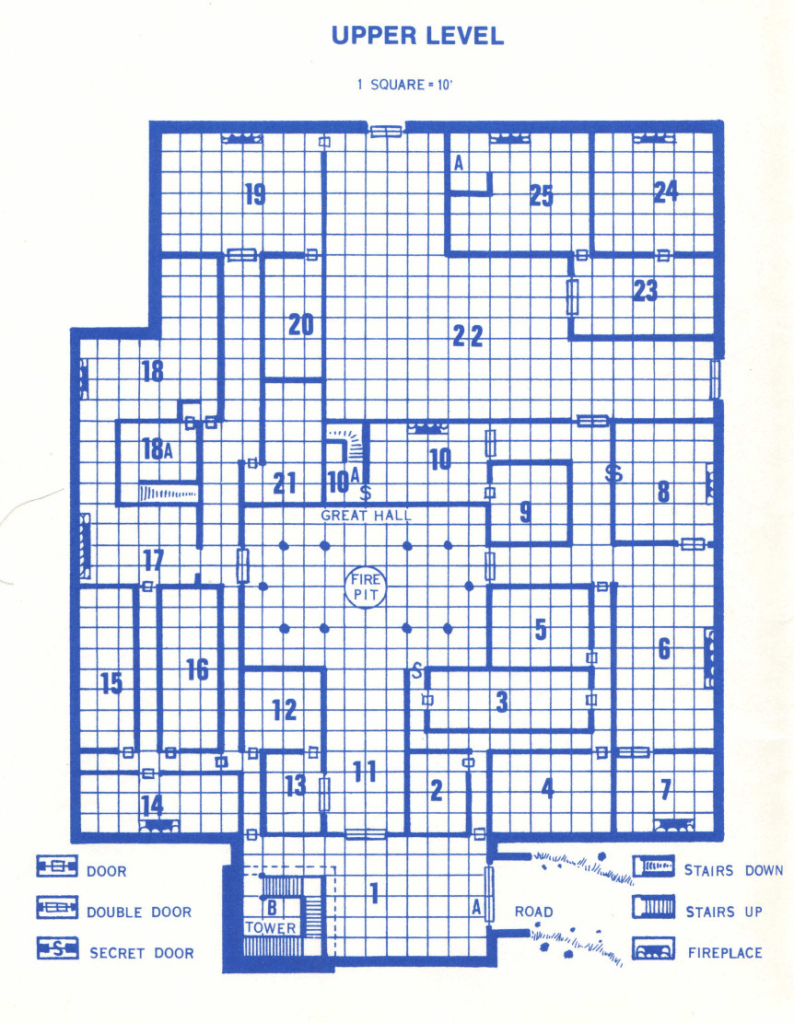

A little before Thracia we also got G1 – The Steading of the Hill Giant Chief by Gygax (1978). This is probably the most “modern” so far in terms of overall design and completeness, though even this module follows Gygax’s philosophy of modules being outlines and toolkits moreso than cohesive locations.

“Module as an example that requires DM fill ins” will come back in stuff like Keep on the Borderlands. Still, this module is recognizable when put next to modern OSR style modules. BG info, encounter tables, and room keys at least give a “complete” vertical slice of what the book chooses to cover:

The dungeon layout is also far more modern than what we’ve looked at up to this point (as far as fully keyed locations go). Below you can see a combination of Vampire Queen‘s boxier, room-oriented layout with the narrow hallways and pathing challenges of UW’s sample. Something like this would definitely fly today:

Substantively, this one is actually simpler than Temple of the Frog. There aren’t really any factions, and the location has one singular context. Still, we are getting a little closer to Thracia in level design. Grognardia has a write up of the contents you can read here.

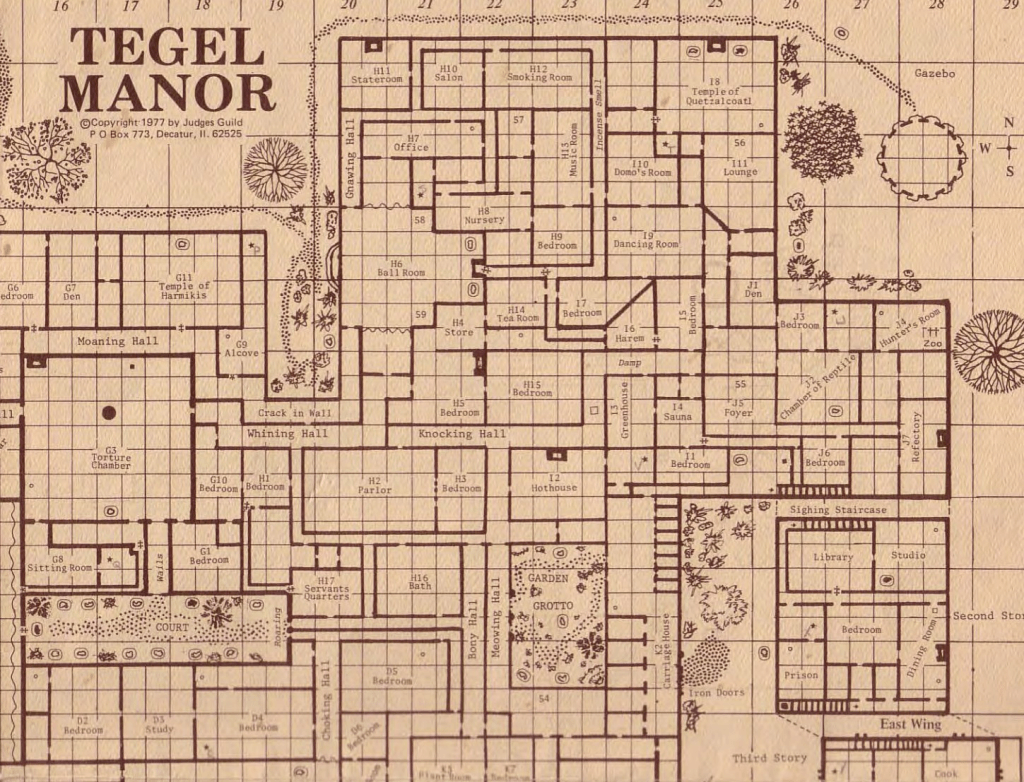

Alright, before we get to Thracia, we have one more book to look at. And boy is this a hefty one. Tegel Manor (1977) is a massive, labyrinthine haunted house that could be fairly called a megadungeon. Pathing and mapping choices abound, with countless paths to take, none of them the same:

Tegel takes an interesting approach to its scenario: there is no lengthy background here, and players only know they’re looting a haunted manor. The module places more emphasis on character interactions, with a whole section on encounters with possibly sympathetic NPCs that are all related. The key is strategically formatted, sparse with a few more detailed rooms. It’s kind of a quantity over quality deal, as there are tons of rooms without a lot going on. We now call this a “funhouse” dungeon, though I think modern equivalents are bit more obviously interactive.

While the player can place the Rump family members with purpose into the rooms, there isn’t a lot of prebaked logic to this dungeon. It’s not the internally consistent slice of a world that we would soon get from Jaquays, though it is sophisticated for this era.

So now we’ve reached 1979, and what does the state of dungeon design look like? Well we started with mostly pathing and travel challenges across tons of bendy, terminal hallways, and super sparse keys. With Temple of the Frog we got a shift to a more naturalistic and organic take on dungeon layouts, meant to evoke a realistic location with internal logic and backstory. Palace of the Vampire Queen took us back to Gygax’s gamier labyrinths but with fewer winding hallways and more emphasis on the room as the unit of discovery rather than turning a corner in a corridor. The Judge’s Guild and Tegel Manor maps made this much more complex, with rooms taking center stage but in layouts that created actual different paths around the location rather than a series of doors to open sitting next to each other. And The Steading of the Hill Giant gave us more modern room keys and location-wide tools and descriptions to help us get a better sense of how this should all fit together.

The building blocks of an incredible dungeon are all here, though scattered across a number of books, magazines collections of pamphlets, half-finished ideas just waiting to be combined into a single incredible adventure. And in Part 2, we’re going to talk about that adventure: The Caverns of Thracia, by Jennell Jaquays.

Pingback: How Jennell Jaquays Evolved Dungeon Design, Part 2: The Caverns of Thracia – Pathika

Pingback: Websites via Bluesky 2025-11-19 – Ingram Braun

Pingback: Sobre el proceso creativo – piedrapapeld20