I want to talk about that scene. If you’ve played Chrono Trigger, you know the one: the one where the kids sit around a campfire and talk about what “entity” could be guiding them on their journey. Why do the time gates they’ve used so far on their quest happen to take them to places where they find allies, clues and tools that allow them to succeed in destroying Lavos?

This scene has sparked almost 30 years’ worth of debate about its deeper meaning. Frustratingly, almost all of this conversation has focused on a very specific lens by which to analyze this scene: who is the “entity” that the characters discuss? Is it Schala and Balthasar, as Chrono Trigger’s sequel Chrono Cross may suggest? Is it the planet, as the Ultimania guide implies? The internet’s concern with the significance of this scene assumes that it poses a mystery in the game’s plot for the players to uncover. While there is obviously a conversation to be had there, as has been had so many times already, I think that presupposing the existence of an entity is missing what is really interesting about this scene: that the characters are reacting to their own existential dread. I’m offering a different way to read this scene: not of characters on the brink of discovering a hidden truth of the game world, but of characters developing spirituality as a defense mechanism against uncomfortable cosmic reality, the same way we do in real life. The main work this scene is doing is to mirror the player’s own existential dread about the things they see in the game and in their own reality by having the game characters embrace spirituality and reject an undesirable answer.

Disclaimer: this article reads the English language SNES version of Chrono Trigger as a singular text. The information dissected herein and the answers produced would be different if it were considering Chrono Cross or the “Chrono” games canon as a whole. Keep this in mind as you read.

The Scene

In 600 A.D., a woman named Fiona is trying to replant a forest that was turned into a barren desert by invading monsters. She laments that it would take centuries of constant, dedicated labor to restore the land to its former lush glory. If the player talks to townspeople in her area in 1000 A.D., they will find out that Fiona tried and failed to carry this project out on her own, limited by her own mortality.

Enter your party. Robo, your robot friend from 2300 A.D., offers to stay behind with Fiona and spend the next 400 years replenishing the desert to turn it back into a forest. In any other game, this would effectively end your time with this character. But in Chrono Trigger, you have time travel! So you jump in your time machine and hop 400 years into the future to pick up your dear friend, who from his own perspective will have gone an unfathomably long time in utter solitude, creating a new haven of plant and animal life nearly from scratch.

When you arrive in 1000 A.D., you find a thriving forest where the desert once stood, with a shrine dedicated to Fiona at its center. On an altar in the shrine is Robo himself, deactivated. Let’s put a pin in the unsettling fact that Robo didn’t run out of battery, fall apart, or anything like that, but is rather simply off, able to be reactivated by Crono and friends. There is no scene showing Lucca repairing him until after he turns back on and greets you.

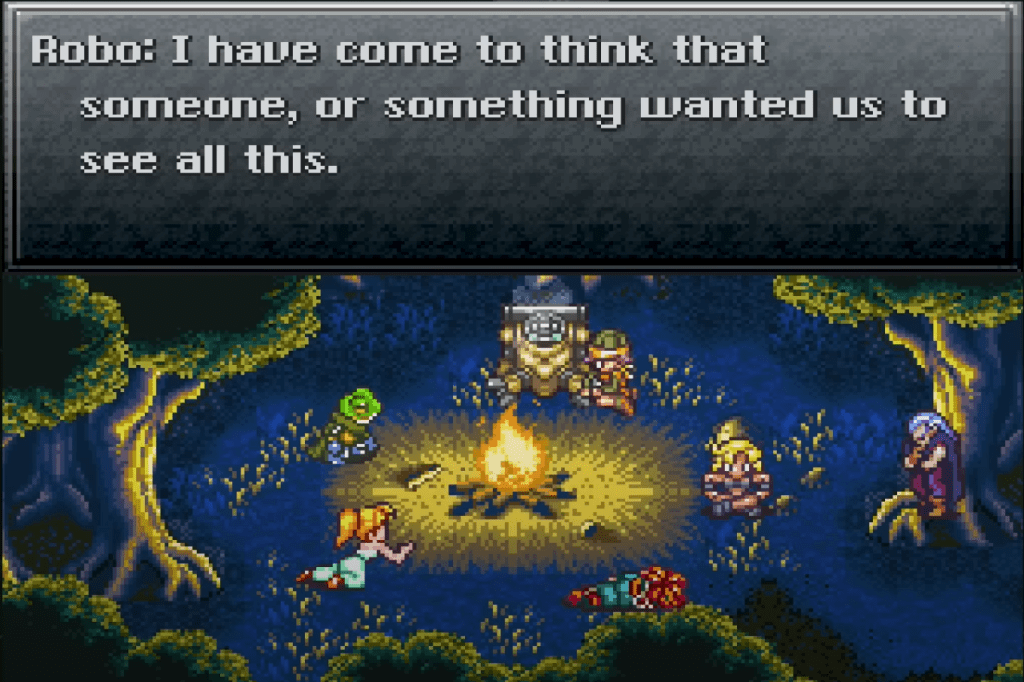

To celebrate their reunion, the group gathers around a campfire in the forest Robo and Fiona replanted. Here, Robo offers a thought that he claims took him 400 years to develop: that the “time gates” the group had used to travel through time for most of the game were not created by Lavos, but some entity with a strong connection to the specific periods the characters are pulled to. The group ruminates on who this “Entity” might be, and whether the time periods the time gates lead to are flashes of memories this entity is re-experiences as it nears its death. At one point during this conversation, Marle ponders if a similar thing will happen to the party when they, too, die. Robo closes the night off with the suggestion that their journey may come to an end when they finally discover the identity of the Entity.

After everyone goes to sleep, Lucca takes a walk into the woods and discovers a curiously red-colored time gate, which takes her to a moment in time not accessible by any other means of time travel in the game: the moment right before her mother lost her legs in a tragic accident in Lucca’s childhood. In this sequence, Lucca is afforded the chance to save her mother and change the timeline, restoring her mother’s legs when one returns to 1000 A.D. afterward. Was this a calculated act of divine intervention on the part of the “Entity”? Lucca’s psyche influencing some sympathetic cosmic force? Pure coincidence? The game never tells us why it happens.

So Who is the Entity?

Let’s assume for the sake of argument that there is an entity at all, that the events of Chrono Trigger are part of some unseen benefactor’s plan. A very common answer to this question, and indeed one offered by the Chrono Trigger Ultimania guide (written over a decade later to incorporate elements from Chrono Cross and Chrono Trigger’s DS port), is that the Entity is the planet itself. This is the most commonly proffered explanation, and has been referred to as the “general consensus” of fans of the game. I don’t dispute that there is consensus, though I think this is a great example of the tendency of fandom toward seeking objective answers and solving plot problems over readings of character and theme. This consensus read takes the statements presented by the characters at face value without considering why they would say these things, and why their statements might be unreliable or involve some element of dramatic irony. It treats the scene not as a window into a development in the characters’ psychologies, but as a lore drop.

Even so, the Earth as the Entity is not a bad theory. The Earth, if personified, is the only “character” that would have witnessed the events of every time period. Lavos is revealed to have been slowly killing the Earth parasitically until Lavos itself gives birth and dies just before the final time period, 2300 AD. So if the Earth is facing its final moments in 2300 AD, the time gates can be read as flashbacks to its most important memories: Lavos’s crash landing in the prehistoric era, Lavos emerging to radically change the landscape in the ice age, Lavos being summoned by Magus in 600 AD, Lavos emerging to scar most of the surface in 1999 AD, and finally the Earth’s imminent death in 2300 AD. The only thing missing here is 1000 AD, though that could perhaps be explained as the Earth specifically reaching out to the player character’s party, if it is indeed guiding them on their quest.

Even if you put aside Chrono Cross and the Ultimania guide, it’s not hard to see why fans of 90s Japanese RPGs would arrive at this conclusion. The Earth as an “entity” that communicates with the protagonists in some form is not out of place in this subgenre, nor in Japanese media in general. And if Lavos were the only actor involved in shuffling the characters between time periods (we know for a fact it is involved at least somehow, as it demonstrates its ability to create gates a couple times), it is odd that the party arrives on Earth some amount of time before Lavos collides with it. Saying the Entity is the Earth clears that up at least a bit, even if it raises its own share of questions.

Now, there is room for doubt here: while personification of the Earth occurs in many, many games from Squaresoft and its contemporaries, it never happens through the game’s authorial voice in Chrono Trigger. The Earth is almost never personified before this conversation, and there isn’t much hint that the party’s ability to defeat Lavos comes from the Earth’s aid other than it maybe creating the gates. In fact, the party learns at some point that the continued existence of humans on Earth at all was originally due to Lavos’s destruction of the reptite species (hence that chapter’s title, “Unnatural Selection?”). So while “the Earth” is as good an answer as any, the game does not take a particularly strong stance on this answer being right.

But I’m not here to sell you on who I think the Entity really is. I’m here to argue that Chrono Trigger acknowledges the very real possibility that there may not be a benevolent entity with an actual plan, or indeed any rhyme or reason to why the protagonists stumble upon the ability to defeat Lavos — that it really could all be coincidence that Lavos’s effect on time caused its own death. I’m here to ask you to consider that Chrono Trigger, through the forest scene and many other events in its plot, is showing you why the characters desire the existence of the Entity, ergo, why the characters want to believe in god.

The Party Wants God

When I say the characters want to believe in god, I’m being slightly reductive. What I really mean is they seek some kind of intelligent pattern that explains why the events of the game allow them to succeed in their quest, as well as why there is meaning to their desire to prevent a disaster that will occur long after they’re all dead. I’m using the word “god” as glib shorthand for this desire, as I think their connection to the “Entity” is a direct analogue to real life human spirituality.

It is probably not controversial to say humans seek “meaning” and “purpose” in their lives at least in part because we are cursed with knowledge of our own mortality. Faced with the sublime scale of the cosmos, we have a tradition of creating grand explanations for our existence, our destinies, and what follows our deaths that extends back over a hundred thousand years. At some point, almost all of us will really, truly find our lives interrupted by the startling understanding of our inevitable deaths, and find some way to cope with that. Many of us will do this more than once, maybe even coming to different conclusions about what this knowledge means each time. For some of us, the answer to this will be something akin to spirituality or religion: some personal connection each of us shares with a cosmic truth, a universal energy or maybe a higher consciousness.

One of the most interesting things Chrono Trigger does with its plot is use the existential threat and enigma of Lavos to inspire such a journey for its characters. This culminates in what the characters say when they encounter the final form of Lavos, where, depending on who is in your party, someone may reveal that Lavos’s DNA is some combination of all life that has ever existed on the planet. This leads to a moment of terror for the party, as seen in the possible lines below (taken from Zeality’s Game Script):

Marle: Are you saying IT'S the reason we're all here? Magus: We were created only to be harvested. All people... ...and all living things... Lucca: Grown like farm animals, waiting to be slaughtered... All of our history... our art and science... All to meet the needs of that... beast... Frog: It...is too much to bear... We have been reared like animals...! Our lives hath been for naught...

It’s pretty reasonable to have this reaction to Lavos. Inside the sea urchan-like outer layer is a humanoid creature, with a head, eyes, arms and hands with fingers. And then inside that they find a humanoid chicken robot, accompanied by two bloodsucking “bits”, one of which appears to be the actual creator of the rest of Lavos. What the hell does this mean? What does this have to do with the rest of what the party has seen? Possibly nothing. While the boss battles allude to enemies and locations in time that the players had seen throughout the game, they are created by an entity that shares no direct connection with any of it — it’s just a big pile of non sequiturs.

Coming into contact with what might be God, Satan, both or neither, most of the characters say something to reaffirm either the meaningfulness of their own existence or the purpose of their fight with Lavos. Check out Robo’s and Frog’s lines in particular:

Robo: Human hands created me...

Which means I am a product of that

thing...I am no different than

Lucca and the others...

I am a part of all living things!!

Frog: My life retain'eth its

meaning...!

We haveth our own will!!

On the nose existential statements are rare in Chrono Trigger. Other than moments like this, the game keeps things lighthearted. These scenes are presented almost like intrusive thoughts: glimpses into the abyss that are brushed aside to focus on what the player is ostensibly really there for: adventure, thrills, comedy. But while they are not the mode for Chrono Trigger’s tone, they keep coming back. When the players rescue Marle early on in the game and restore her to existence, she briefly ruminates on what it’s like to die before shaking it off and saying they should get back to their own timeline. Later, after defeating Magus, Crono has an interesting dream where he ponders what his life might look like after Lavos is defeated and there is no longer an adventure to be on. The answer? He seems depressed, and won’t even get out of bed to go to work, relying primarily on his father-in-law’s wealth to coast through life. Incidentally, we later find out the happiest ending for Crono is having to get in the time machine again to save his imperiled mother, i.e. Crono’s sense of meaning is inextricably tied to his status as the protagonist of an RPG adventure.

The player can brush these things away pretty easily. Of the game’s ~20-25 hour runtime, these moments are brief digressions from the general tone of a Saturday morning cartoon. It is entirely up to the player whether they want to really engage with the questions posed by the existence of Lavos, but the game ensures that there is always something around the corner to cause that unsettling brain itch. Of course, it’s not just the player who has to deal with these “intrusive thoughts”, but the characters as well. Two in particular have arcs where the existence of Lavos challenges their worldview and forces them to think in terms they hadn’t previously considered. Ingeniously, these are the two most logical and science-minded characters in the cast: Robo and Lucca.

Let’s start with Robo. After toiling away at creating life for 400 years, perhaps shortly before turning his switch to the “off” position, he experienced a brain shift that caused him to ask the same question humans do: how can all of this be an accident?

Robo prefaces this statement with the fact that it was caused by 400 years of “experience.” But experience doing what? There’s nothing to show Robo was researching Lavos during this time, nor that was he out on adventures looking for clues. Robo’s 400 years of experience comes from doing the work that Fiona could not finish within her lifetime: replanting the forest. Robo’s 400 years of experience, I would argue, is 400 years spent thinking. Engaging in the kinds of thoughts humans do when they’re left to ruminate on something other than taking care of their basic needs or entertaining themselves. This scene doesn’t depict Robo performing a robotic calculation and informing the party of the statistically certain truth; it depicts Robo becoming more human, and learning to partake in human endeavors like philosophy.

This idea of Robo understanding and internalizing human thought processes is a throughline that begins in his introduction and comes back in Robo’s endgame side quest, where the party must defeat Mother Brain, a genocidal AI who believes the most logical course of action is to eradicate humans to prevent Lavos’s spawn from seeking other planets to destroy, creating a robot-centric “nation of steel, and pure logic.” Mother Brain reveals that Robo was originally programmed to live with humans and study them as a species. Robo rejects her invitation to wipe his memories and rejoin her regime, saying that “humans have taught me much.” Mother Brain’s incredulous reaction notes that Robo has gained the ability to form emotions and decides to kill him to show him “how human [he has] become.” Much later, at the end of the game, we return to that quote from above, “I am no different than Lucca and the others… I am a part of all living things!!” wherein Robo declares his struggle against Lavos to be the same as humanity’s.

Putting the forest scene into this framework, Robo’s conclusion that there must be some kind of purpose to the time gates need not be taken as a game mystery for the players to conclusively solve by looking at the game data, but rather Robo’s intersection with a real life mystery that almost all humans engage with. It’s Robo attempting to find order in randomness and a purpose to his struggle. The scene shows us that Robo’s slow transformation into a human being comes with the same desire for meaning that humans possess.

If Robo is wrong, and the time gates are simply the result of Lavos’s proximity to or presence on Earth, it would make the entire quest of the party an ironic accident, a freak collision of factors and events. The bonds the party forge, the life-changing trauma they experience, the happiness they bring to the many characters whose lives they touch: all of these things just a fluke that saved the world. Robo’s rejection of this possibility is more logical than but qualitatively not super different from real world religious arguments for fate: that the events that shape our lives can’t possibly be just the product of chance.

Let’s turn to Lucca. The genius inventor of the party, Lucca creates the key that harnesses their time traveling power. She also happens to believe for most of the game that the existence of the time gates can be neatly explained by Lavos’s existence. This isn’t isolated to Lucca, as the game will ensure you see this line no matter who’s in your party after Lavos collides with the Earth in 65,000,000 B.C., leaving a time gate in his crater. These quotes are again taken from Zeality’s Game Script:

Marle: This Gate was made by

Lavos.

Maybe Lavos is the source of all

Gates?

Lucca: Now I understand!

The immense energy that Lavos

gives off alters time and creates

Gates.

Robo: It appears that the immense

energy that Lavos radiates alters

time and creates Gates.

That said, a line like that coming from the party scientist’s mouth is particularly credible. It’s interesting, therefore, that Lucca is the only character who will independently come up with the idea of the Entity if Robo does not propose it. How do we know this? Well, if the player never does the Fiona sidequest and never triggers the forest conversation, Lucca brings the idea up in the main ending:

Lucca: I thought Lavos made the Gates... But I guess I was wrong. Marle: What do you mean? Lucca: I think a greater force wanted us to experience those events.

This exchange also happens in exactly one other situation: if the player defeats Lavos without resurrecting Crono, and without destroying the Epoch. In this ending, Lucca is understandably not doing great, uttering this line as she returns to 1000 A.D., leaving Marle alone at the End of Time:

Marle: You're all so heartless! Lucca: It's a fate we can't escape. Someday we will all pass away. Marle......

Later in this ending, Lucca meets Marle at the fair and says the line about the “greater force” just before Gaspar shows up and reveals the way to revive Crono.

So what do we make of this? One way to read this order of events is that Lucca, being the most logical and data-minded character in the party besides Robo, ascertains some truth about the gates that the other characters simply do not have the tools to figure out. She and Robo are the characters who explain this to us because they’re the ones we’re most likely to believe. So when they tell us either in the forest scene or at the end that some greater force is guiding their actions, we can take this as an invitation to figure out who that force is, as it must certainly exist.

Personally, I come at this from the opposite angle: that the most compelling read of this selection of two characters to propose the existence of the Entity is not to assert truth but to assert character. Lucca, a logical and scientific character, undergoes something like a crisis of faith when faced with the idea that her journey might be explainable just by Lavos’s influence. I think that Lucca is also tacitly rejecting the idea that that the Entity might be Lavos himself, not because it’s not feasible, but because the answer is similarly undesirable. It would mean that the entity who may have provided her with the opportunity to save her mother’s legs is also the entity that will one day end humanity if she doesn’t kill it. This is not necessarily to say that I think Lucca’s arc ends with the reveal that she’s become less rational. It’s more that I think Chrono Trigger picks an intelligent character for this arc to argue that spirituality is not necessarily a product of ignorance, but rather intrinsic to being human. This is why this particular element of character development is shared by the smartest woman in the world and the character whose arc revolves around slowly becoming more human.

Spirituality is Good, But We’re All Wrong

What’s interesting about this choice to depict spirituality as a positive thing is that Chrono Trigger is not super optimistic about humanity’s ability to use spirituality to come to correct conclusions. The game celebrates humanity’s tendency towards religion and similar spiritual beliefs, but it almost never confirms any of the specific beliefs seen in the various cultures across time periods as true. In fact, it kind of does the opposite!

Let’s consider the religious ideas we see depicted in Chrono Trigger:

First, we have the beliefs of the reptites in 65,000,000 B.C. While their leader Azala is a scientist who is able to predict that a meteor impact with the Earth will create an ice age, Azala seems to believe that where Lavos will land is a product of the heavens choosing between the survival of humans or reptites. It’s unclear whether Azala is just using figurative language or really links Lavos’s descent to earth as divine intervention, but she’s kind of right. Lavos’s crash landing does in fact cause humanity to take over the planet, though it’s up to the player to decide whether this was mere coincidence, a conscious choice on Lavos’s behalf, or the influence of some even greater being. It’s the first of many ambiguous but impactful occurrences that the game poses in its existential probing.

When we get to 12,000 B.C., we start to see the emergence of more recognizable philosophy and religion. The magical people of Zeal worship Lavos, who happens to be the source of their magic power. This obviously does not end well for them, but it’s worth mentioning that Zeal only falls when they get greedy and dig a little too deep into Lavos’s shell. Up to that point, Zeal pretty comfortably flourishes using Lavos’s powers without repercussions. It’s the first hint we see of Lavos’s relationship to humans as not always being immediately destructive. To be clear, Zeal is still depicted as a flawed society — one that forces the lower class “earthbound” ones to live in caves underground. And even while Zeal’s relationship with Lavos is working out well for them, the court’s wise men seem to think that disaster is imminent. Besides the Lavos-centric religion of Zeal, there is one other important piece of philosophy unearthed in this time period. A secret room contains a diary written by a Nu — the strange and powerful blue creatures that are found in every time period, including 2300 A.D. The diary reads,

All life begins with Nu and ends with

Nu...

This is the truth!

This is my belief!

...at least for now.

This is framed as a joke, but is an important line we’ll come back to later.

Next we have the Kingdom of Guardia and the society of Mystics in 600 A.D. and 1000 A.D., where we see a Christian-adjacent religion appear. However, the cathedral the players see in 600 A.D. is a front for followers of Magus. After the party exposes this, this religion seemingly does not return in the 1000 A.D. version of the Kingdom of Guardia. On the other side of the world, we have the followers of Magus, who we learn is a charlatan posing as their messiah to further his own interests. The only religious structure that seems founded on any kind of truth is Fiona’s Shrine in 1000 A.D., where people worship Robo’s inert body as the creator of the forest alongside the historical figure Fiona. Other than that, nothing that anyone believes in these two time periods appears to last or connect to anything the players can tell is true. Quite the opposite, most religion depicted in these two eras is flagrant misinformation.

By the time we get to 1999 A.D. and 2300 A.D., religion is seemingly entirely absent. It’s hard to say whether it’s just not shown or Chrono Trigger is depicting humanity as trending toward secularism over time, but it seems clear that by 2300 A.D., all of the belief systems of the past have more or less died out. Some NPCs still utter bleakly outdated adages about saving money, but it doesn’t connect to any greater cultural belief system.

What’s interesting about all of this is that these depictions of unconfirmed, short-lived and/or incorrect beliefs exist in the same game where Lucca and Robo complete their arcs by becoming more spiritual. As such, I don’t think the game depicts religion in this way to be antitheistic or antispiritual. Rather, I think it’s proposing that to form these beliefs is a trait inherent to humanity across time and cultures, and this trait is so strong that we get to see the characters develop spiritual beliefs even as they travel the entire span of human history and see various cultures buy into destructive or misguided belief systems. That is the genius of Chrono Trigger’s exploration of spirituality and religion: it is skeptical of it, arguably realistic about it, and yet celebratory of and sympathetic to our desire to be involved with it. The forest scene is the centerpiece of that thesis.

Something I shouldn’t fail to mention, by the way, is that Chrono Trigger has a number of elements to its plot and worldbuilding that do point to forces the characters never see any explanation for. Crono’s Luminaire spell is described as “Holy” magic in the original script of the game, the Life spells involve summoning cherubic angels to bring characters back to life, and Lucca’s special red time gate that takes her back to the exact moment where she can rescue her mother feels pointedly placed there to hint at divine intervention. And finally, of all the philosophies we see presented in the game, there is one that actually turns out to be verifiably true:

In an absolute masterstroke of a gag on a cosmic scale, the one form of life that seems to thrive in every time period, including the End of Time, is the Nu. In fact, even the final form of the game’s most powerful being and optional boss, Spekkio, is a Nu. It turns out that researcher all the way back in 12,000 B.C. was right.

I think I’ve made my point about why I think Chrono Trigger depicts characters developing spirituality, but there’s one more thing we need to consider. One more possibility lurking in the back of the characters’ (and maybe the player’s) minds that triggers the need for religion and spirituality. The need for there to be some benevolent entity.

What if the characters were right that we were seeing some entity’s dying memories, but were unable to guess, or perhaps did not want to correctly guess at whose memories they were?

What if Lavos were the Entity?

Thought Experiment: What if Lavos Were the Entity?

Let me be crystal clear: the point of this article has not secretly been to persuade you that Lavos is the Entity. Rather, I’m going to use this thought experiment to demonstrate how the game has left questions of predestination, higher consciousness, etc. intentionally open and without easy answers. And I think the best way to do that is explore whether the game’s plot can still work if the characters’ conclusions in the forest scene and ending were wrong: that Lavos DID create the time gates, and they simply cannot fathom that the creature they’ve been aiming to destroy is also their benefactor. Or, perhaps the characters can fathom it, but reject it because it just feels very, very uncomfortable. So we’re going to put on our tinfoil hats and explore the worst possible answer, the possibility that might persuade someone to come up with alternative explanations. The thing that makes any other answer seem better.

Let’s review what the characters propose about the Entity. They think that the Entity has some connection to the time periods the gates take you to. They also think the Entity might be dying, which is causing it to see “memories” of those time periods, creating the time gates. Further, whoever created these gates seems to be sympathetic to the characters, as the gates it created allows them to succeed in their adventure and preserve humanity’s existence. It also helps Lucca out in a very personal way.

Those last couple points seem fatal to the proposition that Lavos might be the Entity, but remember that Lavos is a parasite. As we learn from this set of messages during the final battle:

Lucca: Now I understand... It lives on a planet for as long as possible, stealing away the most vital resources... It combined the DNA it found here with its own, and gave birth to those creatures up on Death Peak. Eventually the young must migrate to other planets...to repeat the cycle... Robo: This was Lavos's goal...! Using the DNA of every organism... And achieving the ultimate in evolution! Frog: This be evil! Indeed! This thing possesseth the vitality of all living creatures... It hath harvested DNA from animals, only to further its own evolution! And whilst sleeping, to boot! Magus: ...... So...since the dawn of time, it has slept underground, controlling evolution on this world for his own purpose...

And also from these:

Marle: Are you saying IT'S the reason we're all here? Magus: We were created only to be harvested. All people... ...and all living things... Lucca: Grown like farm animals, waiting to be slaughtered... All of our history... our art and science... All to meet the needs of that... beast... Frog: It...is too much to bear... We have been reared like animals...! Our lives hath been for naught...

- As a parasite, Lavos needs its host to flourish.

Lavos’s survival strategy, whether intelligently planned or purely instinctual, is to “feed” on the energy and DNA to further its own evolution, then eventually “harvest” it. The characters imply that much of humanity’s progress over the aeons has actually been to serve this ultimate purpose. If Lavos is more or less an animal, this means that instinctively it may act to protect humanity until it’s gotten what it needs from them. This may be why, in the chapter titled “Unnatural Selection”, Lavos lands on the reptites, creating the conditions necessary for humans to take over the Earth.

In a way, Lavos as villain only really works dramatically because the player gets to see its life cycle and relationship with humanity play out on a grand scale. We see that it causes immense human suffering and, indirectly, the end of humans, from its emergence in 1999 A.D. to about 2300 A.D. But consider that Lavos has more or less coexisted peacefully with humans for 65 million years before that. The only time Lavos ever erupted and attacked humans before 1999 A.D. is when the Kingdom of Zeal used the Mammon Machine to drill a little too deep into its shell. And it’s not hard to read this as instinctive retaliation, because it only destroys the floating continent where its attackers reside. For the vast majority of human existence, Lavos could have conceivably been on their side.

This is not necessarily to say that Lavos is an active, benevolent god who simply puts a time limit on humanity’s existence. I think it’s easier to read Lavos as mostly animalistic, responding with blunt instruments, so to speak, because most of its time spent below the earth is in hibernation. Thus, I think most of its actions in the game are the product of its subconscious. I don’t think Lavos has much of a goal other than to stay alive until it’s fully mature and ready to spawn offspring, and keep the creatures it’s copying DNA from alive until then. If that’s true, Lucca’s red time gate is not such a strange occurrence anymore. It could simply be that Lavos is, in its sleeping state, subconsciously answering the prayers or desires of a human in 1000 A.D. — a time period where the mission is still to keep its host alive and thriving. In fact, this could also reasonably explain a lot of the “holy” magic the characters use which implies some kind of divine intervention. Since magic was initially introduced to humanity through Lavos (which is why Ayla cannot use it), it doesn’t seem so out there that the effects of so-called “holy” magic might be linked to its powers.

But why would Lavos specifically be tuned in to Lucca’s desires? I think one explanation is that Lavos feels a close connection to the party in general due to Marle’s pendant. The pendant is made from Dreamstone, a prehistoric red rock that seems to channel Lavos’s energy particularly well. This is why the energy-extracting Mammon Machine employed by Queen Zeal is made of it, and why a time gate appears when Marle walks into the transporter with the pendant.

On the topic of time gates, there is an obvious reason why the party initially assumes that they are a product of Lavos before changing their mind: Lavos can create time gates. It does it seemingly out of self defense when Magus attempts to kill him in 600 A.D., and does it later in the story in 12,000 B.C. in reaction to being affected by the Mammon Machine. So even if the characters don’t think the specific gates they use were used by Lavos, they still know in the back of their mind that it can create them.

2. Lavos is dying

Technically speaking, Lavos is already dead. In the far future of 2300 A.D., Lavos has successfully reproduced and its husk has become Death Mountain, where the Lavos Spawn live. However, this isn’t really a satisfactory explanation for why we’re seeing Lavos’s memories in the time gates, because they don’t already exist at the beginning of the story. So who’s prematurely dying when the inciting incident happens in 1000 A.D.? I think, again, that it’s Lavos. Remember that the Dreamstone that comprises the Mammon Machine is something that can awaken and prompt some kind of reaction from Lavos. I think this reaction is self-defense, ergo that the Dreamstone is a threat to Lavos. So when Marle walks into the teleporter and enters whatever wormholey sci-fi nonsense the teleporter interacts with, the Dreamstone comes close enough into contact with Lavos to trigger a time gate, a thing we later see it use as a defense mechanism in the Ocean Palace scene to send the three gurus to different time periods.

So if Lavos is dying, why do the time gates appear in those specific time periods? I think there’s a decent enough explanation for why each period is important to Lavos:

- 65 Million B.C.: Lavos is presumably approaching the planet, which might explain why the first time gate is on a mountain. Later, when it lands, there’s a time gate in the crater.

- 12,000 B.C.: The Mammon Machine threatens Lavos’s life, causing it to wake up prematurely.

- 600 A.D.: Magus wakes Lavos up prematurely again in his attempt to kill it.

- 1000 A.D.: Only creates the time gate here due to brief interaction with Dreamstone.

- 1999 A.D.: Full maturation, wakes up to eradicate humanity and terraform the planet so its children can live there.

- 2300 A.D.: Possibly Lavos’s death, though we don’t know when exactly it happens.

3. Lavos as the ironic cause of its own death is not unusual for Chrono Trigger

The last thing to answer here is possibly the most obvious one: if Lavos is the Entity, why would the Entity lead the characters to the resources necessary to cause the Entity’s death? I think this is where it becomes particularly important that Lavos is acting subconsciously and instinctively. The actions the characters take don’t directly threaten Lavos until the very end of the game, where they challenge him head on. Until that point, they’re just humans existing in time periods where Lavos and humanity are not necessarily enemies. I think it’s very possible that, in cultivating humanity, including its entire culture, art, technology, etc. (as Lucca notes in the final battle), Lavos will unintentionally create things that will allow them to kill Lavos one day. The time gates are the most obvious example of this, but things like the swords, guns, and magic that the characters use are also indirect results of Lavos’s influence. While is this very ironic, it’s ironic in a way that many things that happen in Chrono Trigger are. Here are a few other examples of this happening to other characters in the game:

- We know that Guardia creates a criminal justice system because of Crono’s exposure of Yakra’s plot in 600 A.D., which means Crono inadvertantly caused his own imprisonment in 1000 A.D.

- Mother Brain, the artificial intelligence that intents to commit genocide against humans, reveals near the end of the game that robots like Robo were originally constructed to spy on humans to aid in their eventual deaths. But Robo is a “defect” who became sympathetic to humans instead, aiding Crono’s party in defeating Mother Brain and ending the threat to humanity. In other words, a robot created by one of the game’s villains to end humanity is its unintentional savior.

- The only weapon that can disrupt Magus’s magical barrier is the Dreamstone, the mineral associated with the Zeal Royal family (and with Marle’s entire family line, going back to Ayla) and from which the Zeal royal family’s pendant is made. In other words, Magus is defeated by his own family’s heirloom stone because it cuts through the magical protection his family gained from his sworn enemy, Lavos.

All this is to show that Lavos causing its own death unintentionally is not so unusual for Chrono Trigger. By this read, Lavos is not a terrifying angel of death or calculating supervillain, but an organism trying to live out its full life span like any other character in the game. Lavos is just doing it on a much, much longer time scale and in a way that will eventually, a very, very long time after its first meeting with humanity, will cause humanity’s destruction. Given that, Lavos’s actions seem as likely to lead to its own ironic defeat as Magus’s or Mother Brain’s.

4. Lavos is Directly Analogized to Real World Wrathful Gods

One of the things that makes Lavos an effective foil to characters developing a sense of spirituality is that Lavos is already presented via overt mythological overtones. He ends the world in 1999 A.D., which at the time of Chrono Trigger’s publication was entrenched in pop culture as an apocalyptic year, most famously by Nostradamus (predicting that a “King of Terror” could come from the sky), but also by a variety of sects connected to various Abrahamic religions. In 600 A.D. and 1000 A.D., the party learns that the mystics revere Magus as a Christ-like messianic figure who will herald the coming of Lavos. Lavos himself occupies a space common in many mythographies: the cause of the transition from antiquity to the modern era. In place of a flood myth wherein humanity’s evil is washed away as part of God’s judgment, with one or a few good humans being spared through divine intervention, Lavos destroys the disparate and inequitable Zeal society when its greed takes it too far. And when the party finally encounters Lavos in a direct battle, one of his attacks is a direct reference to Isaiah 24:18-20: “Destruction rains from the heavens.”

The point here is not that Chrono Trigger is definitively presenting Lavos as God, but rather that the evolution of the beliefs of Lucca, Robo and the rest of the party are happening in the face of a creature who is directly analogized to real world gods but who seemingly shouldn’t be. The script’s implication might even be that that our own real world belief systems might be connected to some destructive, parasitic force, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we should give up on the idea of spirituality entirely. I would suggest that what makes Chrono Trigger’s exploration of the topic so interesting is precisely that Lucca and Robo see what the average internet atheist in their position might take as definitive proof of an indirectly worshipped god not only being a lie, but also evil in concept, and their response is to actually form spiritual beliefs for the first time.

Conclusion

Obviously, the conclusion is not that Lavos is the Entity. I think Chrono Trigger would feel a lot less interesting if that answer were clear. Rather, my thesis is that Chrono Trigger endeavors to make the player feel the existential dread of its fictional protagonists, to ask the same uncomfortable questions and to come up with their own tenuous answers. The true purpose of the scene in the forest is to inspire this dread and uncertainty by using the game characters as analogues to the player. The identity of the Entity is not the point of the scene; it’s the fact that the characters think there may be one at all, in spite of all they’ve seen.

Most role-playing games simulate a journey, making the player feel as though they’ve lived fantastic events and overcome incredible adversity across an adventure that is epic in scope. Chrono Trigger does all that, sure. But what Chrono Trigger does that’s a bit rarer is forcing the player to reckon with the emotional impact of seeing humanity from such a wide scope, and offering the player a chance to experience the same uncertainty in the face of the sublime that their avatar does. The game would not be nearly as effective at doing this if the Entity’s identity or existence were clearer. The ambiguity Chrono Trigger offers the player is, if anything, one of its most realistic elements, a tiny peek into the uncomfortable detachment of the cosmos for its young target audience.

So while internet consensus may consider this mystery solved, I think it just means Chrono Trigger’s depiction of humanity as yearning for “right” answers, often settling on one that offers comfort, is spot on.

You awesome person. Thanks for writting this article; its so crazy. Let me take a free moment sometime this week to read the whole of it insterad of skimming over

LikeLike